Heart Attack

Myocardial Infarction (MI)

Overview

Did you know that every 40 seconds, someone in the U.S. has a heart attack?1 This equates to about 805,000 people a year, and about 1 in 5 heart attacks are silent, meaning the person was unaware of it.1 A heart attack, or myocardial infarction (MI), results when a complete or partial blockage suddenly forms in the arteries that supply blood to your heart – the coronary arteries. Without blood, the heart muscle begins to function poorly or stops working permanently. That’s why every second counts regarding heart attack treatment and why it’s important to seek immediate medical attention if you’re having heart attack symptoms—especially if your symptoms persist for more than 15 minutes. To receive the best care, you have about 90 minutes from the onset of the heart attack for a cardiologist to restore blood flow to the heart before critical heart tissue forms a permanent scar or is severely damaged. However, the good news is that today, your chances of surviving a heart attack—and surviving it well with a return of heart muscle function—are more significant than ever.

Blockages are caused by a disease process throughout the arteries in your body called atherosclerosis, in which plaque—a fatty substance—builds up in the arteries. This plaque narrows the arteries, leaving less room for blood to flow. A plaque can be topped with a thin, fibrous cap that ruptures. With rupture, exposure of atherosclerotic debris to the bloodstream can cause platelets (a component of blood that assists with clotting) and red blood cells to collect at the site of the rupture, cutting off blood flow through the artery into the heart muscle. Alternatively, part of the plaque may break off in the artery. This piece of plaque can then lodge in a narrowed portion of the artery and blood will begin to clot around it. This blood clot (thrombosis) can partially or completely cut off blood flow through the artery. When blood flow is reduced to the heart muscle, this is called ischemia, and when flow is completely cut off, this is called MI.

Types of heart attacks

Not all heart attacks have the same symptoms or severity, but ultimately, the seriousness of the heart attack is judged by the amount of heart muscle permanently damaged. If you have a heart attack, treatment will depend on the type and severity of your heart attack. The following describes different types of heart attacks:

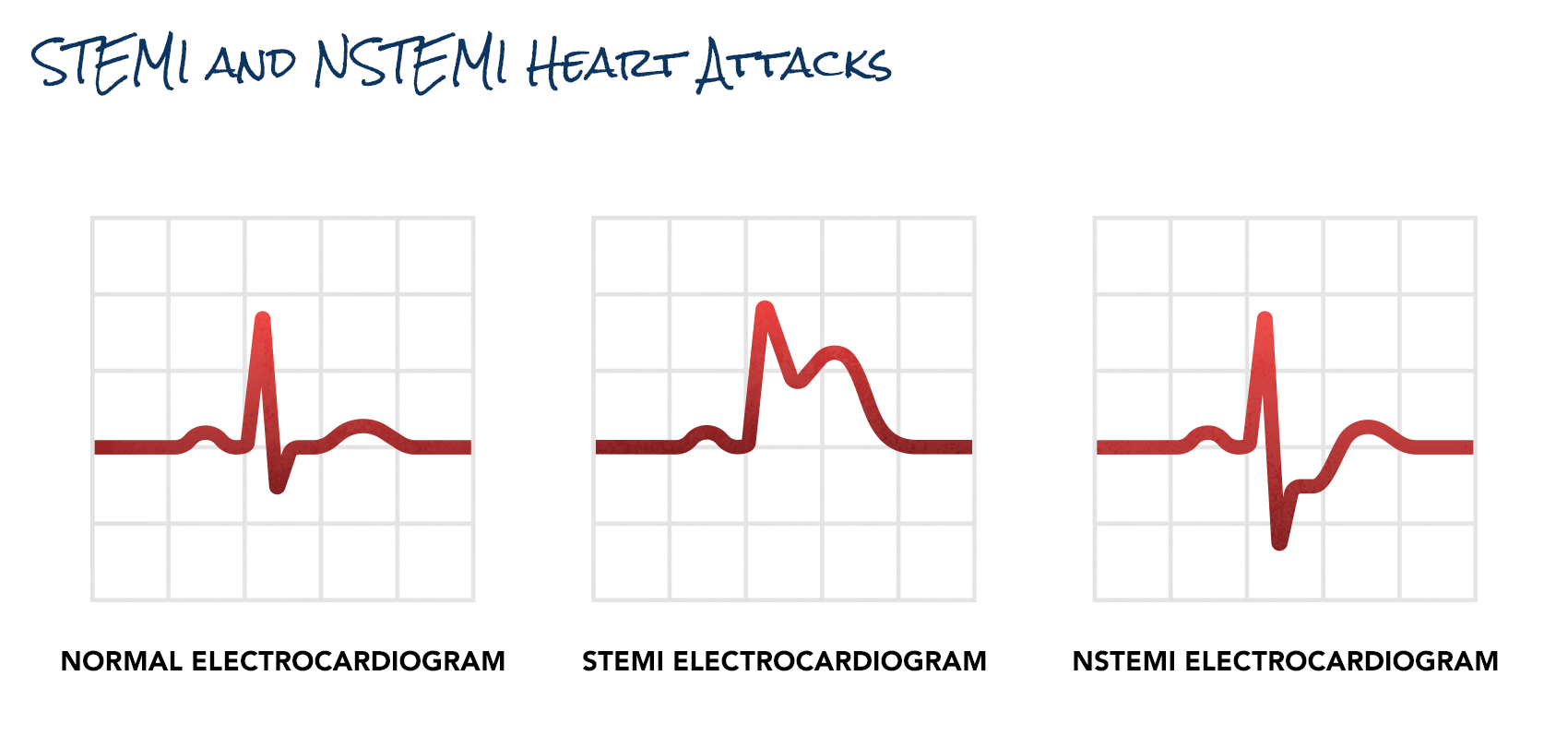

- STEMI heart attacks – An ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is a serious form of a heart attack in which a coronary artery is completely blocked, and a large part of the heart muscle cannot receive blood. “ST-segment elevation” refers to a pattern on an electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG). This heart attack requires immediate, emergency reopening of the artery, which restores blood flow through the artery (revascularization).

- NSTEMI heart attacks – A non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) is a type of heart attack that doesn’t show ST-segment elevation but may show ST segment depression on an EKG and often results in less damage to your heart. In NSTEMI heart attacks, the coronary artery blockages are likely partial or temporary.

- Coronary artery spasm – When the artery wall tightens, and blood flow through the artery is restricted—potentially leading to angina (chest pain) or the cutoff of blood flow—so a heart attack results. Coronary artery spasms generally come and go, and there may not be a plaque buildup. It may not be discovered by the same imaging test (angiogram) that is typically performed to check arteries for blockages or narrowing.

- Demand ischemia – This type of heart attack may or may not have blockages in the arteries present. It occurs when your heart needs more oxygen than is available in your body’s supply. It may occur if you have an infection, anemia, or tachyarrhythmias (abnormally fast heart rates). Blood tests will show the presence of elevated cardiac enzymes that indicate damage to the heart muscle.

Cardiac arrest vs. heart attack

Cardiac arrest is not the same thing as a heart attack—the biggest difference is that in cardiac arrest, your heart stops beating, while during a heart attack, your heart keeps beating. But cardiac arrest can occur due to a heart attack, or it can also occur as a primary event. In other words, cardiac arrest can occur for other reasons besides a blockage in your artery. Examples include electrolyte disturbances, low or high potassium, low magnesium, congenital abnormalities, or poor heart pumping function.

A heart attack can cause life-threatening arrhythmias (abnormal heart rhythms) such as ventricular tachycardia (VT) or ventricular fibrillation (VF). These arrhythmias will result in a cardiac arrest within a few minutes because your heart is not pumping blood to the lungs to pick up vital oxygen that circulates back to your heart and your body. When this occurs, an automated external defibrillator (AED), CPR, and a call to 911 are immediate lifesaving measures.

Seconds count in treating both heart attack and cardiac arrest. With cardiac arrest, the odds of survival go down by about 10 percent every minute until the person is resuscitated. After 10 minutes, the risk of permanent brain injury is very high.

Other conditions that mimic a heart attack

Many medical conditions can mimic a heart attack, some of which may indicate something urgent.

- Unstable angina – Angina is chest pain caused by a lack of blood flow to the heart due to narrowed or blocked heart arteries. Most commonly, it results from coronary artery disease (CAD). Unstable angina requires immediate attention because it can be the first sign of a heart attack.

- Stable angina – This type of angina occurs with exercise and is relieved with rest. Symptoms are easily reproducible with the same type of activity and have been relatively stable for several months. For example, you may report chest discomfort every time you walk 10 minutes or uphill, but the pain always subsides with rest.

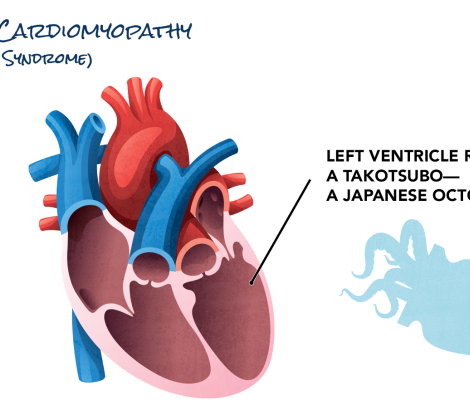

- Broken heart syndrome (takotsubo cardiomyopathy) – Occasionally, a person may arrive in the emergency room with the symptoms of a heart attack, but no blockages will be discovered in the arteries that supply blood to the heart. Instead, the heart’s main pumping chamber, the left ventricle, contracts in an unusual pattern. While this syndrome is not well understood, researchers think the heart’s left ventricle may be “stunned” and unable to function because of a surge of stress hormones after the patient experiences a severe emotional or physical trauma such as a death of a loved one or an automobile accident. The syndrome usually resolves quickly and without lasting damage to the heart, but in rare cases, it can be fatal.

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and esophageal spasm – GERD is a condition in which you have chronic heartburn, while an esophageal spasm occurs when your esophagus, the pipe that carries food from your mouth to your stomach, strongly contracts. Either of these conditions can cause chest pain and be hard to distinguish from a heart attack since the esophagus runs directly behind the heart within the chest.

- Pulmonary embolism (PE) – A PE can cause chest pain that mimics a heart attack and is equally serious. It’s a blood clot in an artery in the lungs, which cuts off blood flow, causing lung tissue to scar or die. This condition requires immediate medical attention.

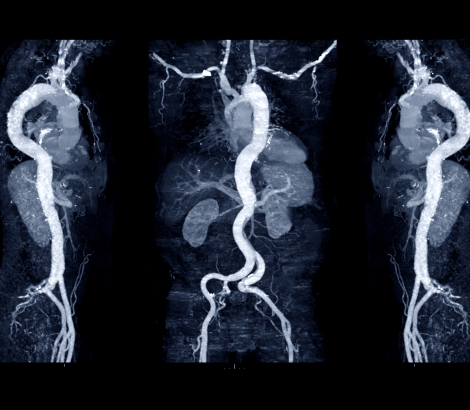

- Aortic dissection – The aorta is the main artery that brings blood from the heart to the rest of the body, and if there’s a dissection—or tear— in the innermost layer, blood pumped from the heart may separate one layer from another, causing a tearing chest pain that sometimes goes to the back. The tear can also extend up to the carotid arteries to the brain, back to the coronary arteries of the heart, or down to the arteries of the legs, which may cause a heart attack, stroke, and even death. It is a life-threatening medical emergency that requires immediate treatment.

- Musculoskeletal pain – Chest pain may be as simple as a pulled chest muscle. Costochondritis, a condition where inflammation in the cartilage that connects the ribs to the breastbone, can also feel like a heart attack.

- Psychological disorders – Panic disorders, anxiety, depression, emotional stress, or other psychological disorders may also cause chest pain. In these psychological disorders, chest pain is not related to angina or digestive causes but seems triggered by emotional stress.

Remember, if you’re experiencing symptoms of a heart attack, dial 911! And if you can, chew an uncoated aspirin tablet while you wait for emergency medical technicians (EMTs) to arrive, as this can help slow blood clot formation.

Did you know?

The prevalence of heart attacks varies across sex* and race:

- Black women are more likely than white women to have a heart attack.2

- Black adults are more likely than white adults to die from a heart attack.2

- Young Hispanic women who have a heart attack face a higher risk of dying than young Hispanic men. They’re also more likely to die than young Black and white adults.2

- Heart attacks caused by heart conditions other than coronary artery disease (CAD)—known as myocardial infarction in the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease (MINOCA)—are more common in Black, Hispanic/Latino, and Asian people.3

*The term “women” in the context of “women’s cardiovascular health” applies to individuals assigned female at birth (AFAB) who have a female biological reproductive system, which includes a vagina, uterus, ovaries, Fallopian tubes, accessory glands, and external genital organs.

*The term “men” in the context of “cardiovascular health” applies to individuals assigned male at birth (AMAB) who have a male biological reproductive system, which includes a penis, scrotum, testes, epididymis, vas deferens, prostate, and seminal vesicles.

Stories of Hope and Recovery

Jack Hatley began having chest pain and was certain he was having a heart attack. At the hospital, his interventional cardiologists performed an angioplasty, placing two stents to open a blockage.