Stories of Hope and Recovery

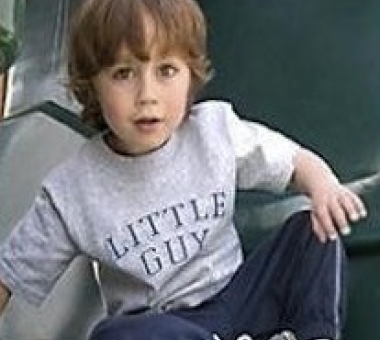

Xander Bowen

Saved by Heart Surgery and Catheterizations

With every inch her son grows taller. Every pound he adds. Every day he gains strength.

These are things some mothers may take for granted. But for Lisa Bowen, they are reasons for joy. Joy that Xander is here, standing three feet tall, weighing nearly 30 pounds, and approaching age 4. And joy that, with more time, Xander will grow bigger and stronger—and better prepared for his next major heart surgery.

Born with a heart defect called truncus arteriosus, Xander underwent surgery two days after birth. In truncus arteriosus, a single large vessel carries blood from the heart to the body and the lungs. During Xander’s operation, surgeons repaired the defect, splitting the single vessel into two “normal” channels for blood flow—one from the heart to the lungs and another from the heart to the body. To create a new pulmonary artery, the vessel from his heart to his lungs, they used tissue from a donor, a procedure called a pulmonary homograft.

As Xander left the hospital a month later, his surgeons said they would need to see him again in three to five years. At that time, the vessels they had created would need to be replaced with new ones designed to fit his larger body. Until then, all he needed to do was grow.

But life was not to be so simple. At three months, Xander began sweating excessively and not eating. The diagnosis: congestive heart failure and a blocked right pulmonary artery (between his lungs and heart).

Xander’s condition has taken us into worlds we never expected to be in.

Lisa BowenInstead of placing Xander through the trauma of more “open” surgery, doctors opened the blocked artery using a less invasive procedure called angioplasty. To clear the blockage, an interventional cardiologist inserted a small, thin tube with a tiny uninflated balloon on its tip into a blood vessel in Xander’s thigh. After guiding it through his arteries to the blockage, the physician inflated the balloon. The force of the inflating balloon compressed the blockage against the artery wall. With his blood flow restored, Xander’s heart could function normally.

Two weeks later, though, Xander began to vomit. Doctors determined the problem was again blockage in his right pulmonary artery and that the artery should be propped open with a stent, a small, flexible mesh tube that acts like a scaffold inside the vessel. Again, an interventional cardiologist performed the procedure, inserting the tiny tube and working it through Xander’s vessels to re-open the pulmonary artery and place the stent.

Each of these procedures (called catheterizations)—plus the four he has needed since to keep blood flowing to and from his heart—have bought precious time for Xander. Those procedures have included enlarging the pulmonary artery stent as Xander has grown, placing another stent in the pulmonary homograft, and performing angioplasty to open a narrowing in his aorta.

“His cardiologist is thrilled we’ve been able to get him bigger before the next major surgery to replace his pulmonary homograft,” says Lisa.

She reflects on all that has happened: “Xander’s condition has taken us into worlds we never expected to be in,” she says. “We are family with the people whose son was the donor of the tissue the doctors used to create Xander’s pulmonary artery. And we have become close with other families with children with truncus arteriosus. Ten years ago, kids did not survive this. Now just to see these kids play is incredible.