Heart Valve Disease

Overview

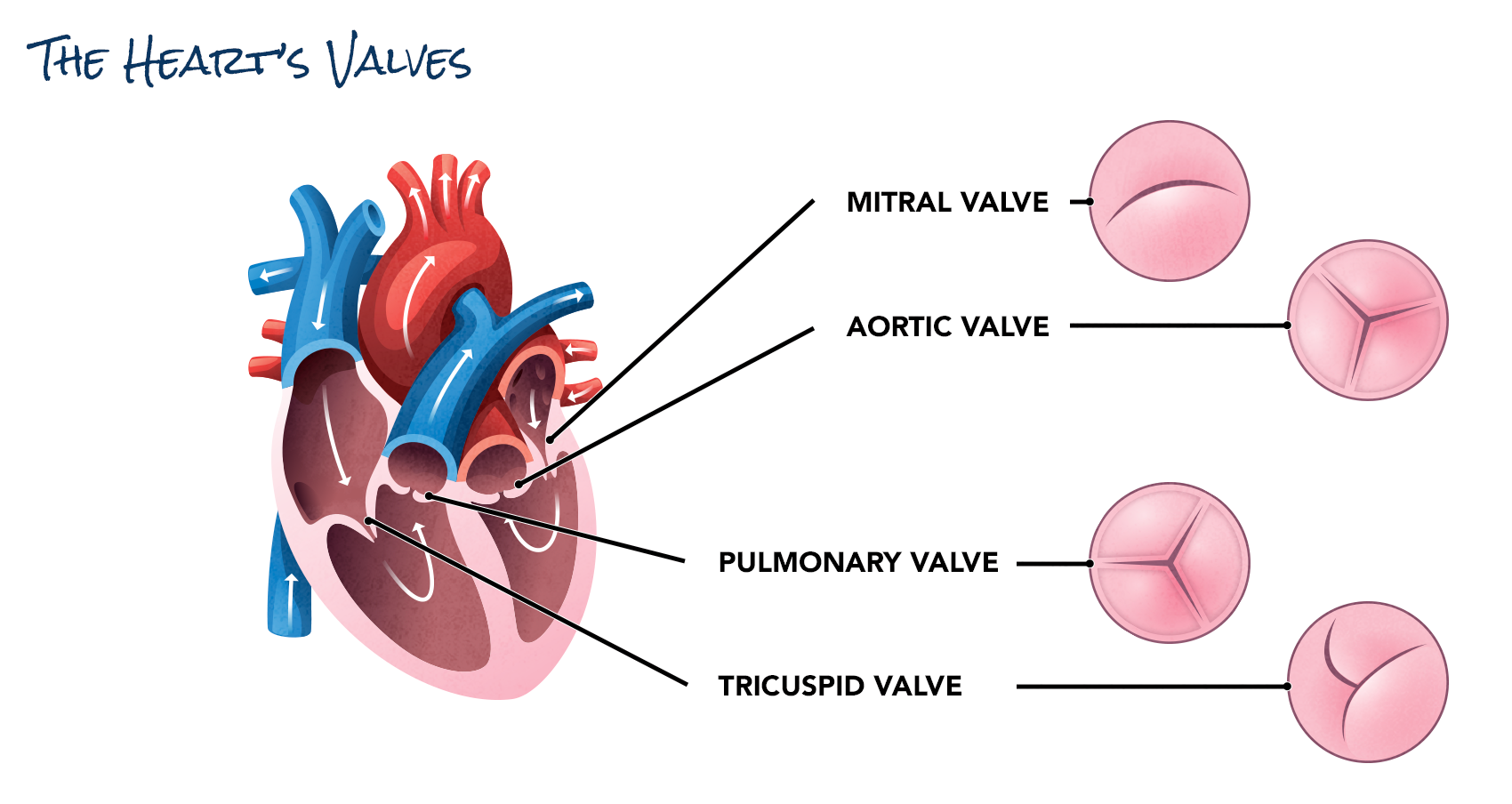

The heart's four valves regulate the direction and flow of the blood that replenishes the oxygen supply throughout your body. But when these valves are defective or don't work the way they should, the heart has to work harder to compensate for the faulty valves, which can weaken your heart, putting it and your other organs at risk. This is known as heart valve disease, which can increase your risk for certain conditions such as heart failure, sudden cardiac arrest, and stroke.

Heart valve disease classifications

Approximately 2.5% of people in the U.S. have heart valve disease, and about 28,000 die from it each year.1 There are several types of valve disease, which can affect one or more of the four valves in the heart. They are classified into two types of valve dysfunction:

- Regurgitation – The valve’s leaflets don’t fully close or the edges don’t fully meet, which causes blood to leak back into the chamber it came from.

- Stenosis – The valve’s leaflets can’t open fully to allow enough blood to flow.

Some problems with the valves are present at birth (congenital valve disease), while others develop over time as we age (acquired valve disease). Both regurgitation and stenosis valve dysfunction cause turbulence in the blood flow, which produces what is known as a heart murmur.

Types of heart valve disease

Acquired valve disease

Acquired heart valve disease means you were born with normal heart valves, but problems developed over time due to family history or illness or aging. Acquired valve diseases more commonly affect the aortic or mitral valves.

This type of heart valve disease affects the aortic valve, which sits between the lower left chamber of your heart (left ventricle) and a major blood vessel called the aorta. The aortic valve acts like a gatekeeper and opens to release blood from the left ventricle and closes to keep any of the blood from washing backward.

This type of heart valve disease affects the mitral valve, which is one of the four valves that regulate blood flow through the heart. It controls flow from the left upper chamber of your heart (left atrium) to the left lower chamber (left ventricle). In a healthy heart, once the blood flows to the left ventricle, the mitral valve seals shut so that when the left ventricle contracts, the blood is pumped out only through the aortic valve out to the body, as it should be, and can’t flow back into the left atrium.

Congenital heart valve abnormalities may result from valves that don’t fully form or are the wrong size or shape. This may restrict blood flow or result in blood flow washing back into the wrong chamber.

This type of heart valve disease affects the tricuspid valve, which lies between the heart’s upper right chamber (right atrium) and the lower right chamber (right ventricle). If this valve didn’t develop properly before you were born, it might not have an opening to allow blood returning from your body to be pumped to your lungs to collect oxygen.

Pulmonary atresia

This type of heart valve disease affects the pulmonary valve, which lies between your lower right chamber (right ventricle) and the pulmonary artery that leads to your lungs. If this valve didn’t form properly before birth or if there’s a hole between the two bottom chambers of your heart, you may not have a direct connection between the heart and the lung’s blood vessels.

If you’re born with a pulmonary valve that’s thick, the opening in the valve is too narrow for all blood to flow normally from the heart through the valve and to the lungs.